Home

Ignoring Learned History: A Significant Oversight in Animal Welfare Decisions

By Mark Simmons

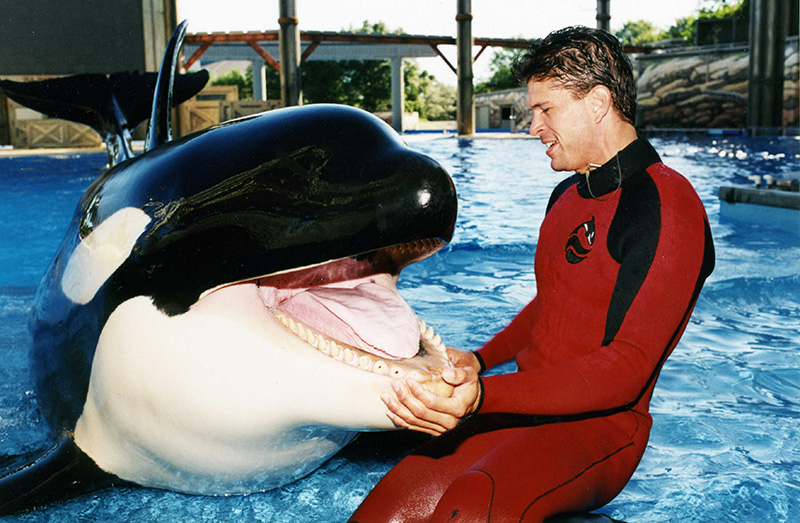

The author with a killer whale at SeaWorld Orlando |

I was hired in 1987 as an apprentice trainer in the Animal Behavior department at SeaWorld in Orlando, Florida. Not long after, the title, “Animal Behavior” was modified to “Animal Training.” To this day I don’t know the exact reasons for the change, but it seemed then, as it does now, to be a dumbing down of our profession.

Maybe it was right to change the department title to Animal Training; at that time little attention was given to managing that larger sphere of influence. Fast forward 36 years to 2023. After recently attending the joint IMATA/ABMA Conference in Atlanta, Georgia and watching presentation after presentation it is abundantly clear that a comprehensive view of behavior management is very much leading the field today. Thankfully, we trainers inherently recognize that the factors that shape behavior are complex, multilayered, and always at work influencing outcomes. That’s the “how” of learning, but “what” is learned remains unique to each animal.

Recognizing this truth is central to providing for the well-being of individual animals, yet outside of our professional field, behaviorism is largely absent from conversations concerning animal welfare. Tokitae is the most recent example. Tokitae (“Toki” to her caregivers, publicly known as “Lolita”) is a killer whale (Orcinus orca) that has lived at Miami Seaquarium for over 50 years.

Tokitae is a female killer whale (Orcinus orca) from the L pod of the southern resident orca population. She has resided at Miami Seaquarium since September 1970. Tokitae is a female killer whale (Orcinus orca) from the L pod of the southern resident orca population. She has resided at Miami Seaquarium since September 1970. |

On 30 March 2023, Miami Seaquarium announced their intention to relocate Tokitae (and two Pacific white-sided dolphins) to the waters of the Pacific Northwest. On 30 March 2023, Miami Seaquarium announced their intention to relocate Tokitae (and two Pacific white-sided dolphins) to the waters of the Pacific Northwest. |

In late March it was announced that Miami Seaquarium, in partnership with “Friends of Tokitae” (FOT), would return Toki and two Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) to the Pacific Northwest. In response to questions about the animals’ possible release to the wild, Miami Seaquarium indicated that the three animals would initially be housed in a sea pen, but would ultimately allow Toki to “show [FOT] the way.” As in so many cases involving the lives of zoological animals, the stated “benefits” to Toki are based on an interpretation of killer whales from the field of ethology; the study of wild whale behavior set in a vastly different environment with conflicting requirements for survival.

Like any animal (or person) Toki is a child of her history, and after half a century spent with humans, hers is infinitely unique. Given the modern body of knowledge in animal sciences, I contend that behaviorism is the single most qualified branch necessary to fully evaluate the impact of life changes for any animal, especially when the scale of the proposed change is so immense.

There are many prerequisite considerations when planning major changes to an animal’s habitat and routines. Health is undoubtedly a factor, as are assessment of physical, nutritional, and phylogenetic history. Although one or more of these categories of biology may render the animal unsuitable, they do not collectively or individually affirm the possibility of success without considering the animal's ontogenetic history. Proposing a life change of the magnitude suggested for Toki must include an impact assessment of her welfare beginning and ending with a thorough evaluation of her distinctive learning history.

Ecotype is defined as a distinct group within a species that is adapted to a specific ecological niche or habitat, often distinguished from each other by their physical, physiological and/or behavioral characteristics. Imagine if “zoological orca” were recognized as an ecotype. The distinction could help the wider scientific community understand the crucial significance of an animal's ontogenetic history.

IMATA is an association of individual professionals in the field of animal training and behavior. Its members are experts in zoological animals, specifically, those that have a highly specialized history and long-standing relationship with humans. Further, Miami Seaquarium has, at least for a time, had their internal program for the development of their animal training staff accredited by the association. Given the high profile and high-risk nature of the move announced for Tokitae, it seems obvious that consultation with IMATA would be pursued. To my knowledge, no such consultation has been sought by anyone involved in the proposed endeavor, including Miami Seaquarium, FOT or the City of Miami.

When the most critical part of solving a problem is completely left out of the solution, it can be described as a significant oversight causing decision makers to focus too narrowly on a single attribute while disregarding other vital aspects. The failure to understand the magnitude of influence exerted by an animal’s learned history is what led to the abuse and ultimate death of Keiko during his attempted release. Sadly, too many cases exemplify the same disregard (even contempt) for behaviorism when it comes to zoological animals placed in sanctuaries or returned to the wild.

While experience teaches me this plan for Tokitae is not beneficial to her well-being, I would gladly settle for the stakeholders in Miami to seek a forensic assessment of the risk/benefits conducted by qualified experts in the field of behavioral sciences; that would be an important step in the right direction. It just so happens that I know where these experts can be found.

Editors Note: Mark Simmons is a longtime IMATA member and the author of Killing Keiko: The True Story of Free Willy’s Return to the Wild. He was director of husbandry on the Keiko Release Project in Iceland and a former killer whale trainer at SeaWorld Orlando, and has consulted worldwide on marine mammal issues, legislation, and welfare.

Many important questions about the viability of Miami Seaquarium’s initiative to relocate these animals remain unanswered. IMATA’s understanding is that the three animals mentioned in this column are not suitable candidates for return to the wild, and any plan to relocate these animals would take a tremendous amount of thought, planning, coordination, and consultancy with experts and stakeholders from multiple organizations including the International Marine Animal Trainers’ Association (IMATA), the Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums (AMMPA), the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine (IAAAM) among others.

IMATA is engaged in ongoing, active dialogue with Miami Seaquarium to seek full understanding the specifics of these animals’ future care, behavioral management, and the opinions of the expert veterinarians who have been consulted as to whether any potential move could jeopardize their wellbeing.

Photographs featured in the this column were provided courtesy of Nicole Fernandez, Mark Simmons, and Marni Wood.